What Exactly Is The Reverse Taper?

Here's how to make your post-race comeback.

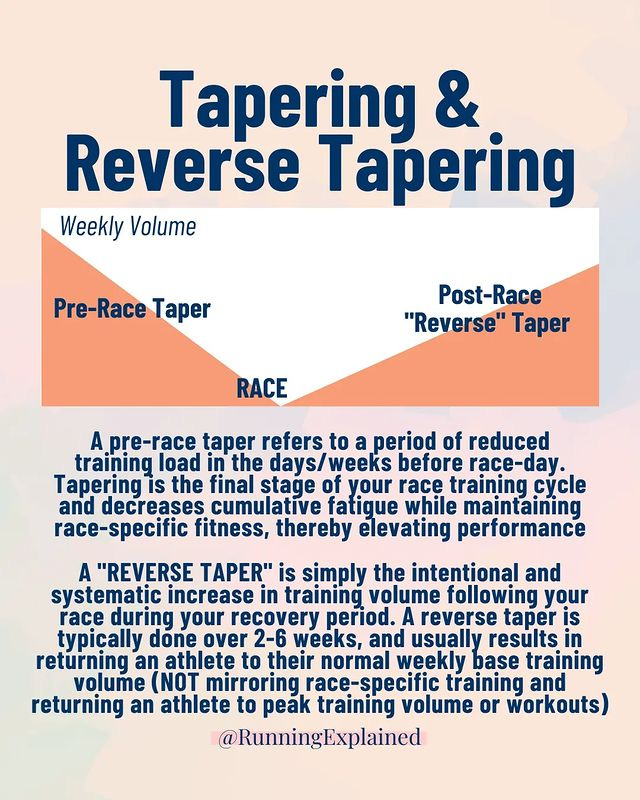

Runners tend to have a love/hate relationship with the race taper—that period of scaled back volume before the big day—but often completely overlook the reverse taper, which is equally important.

Technically, a reverse taper is not actually a taper: The phrase is simply a catchy way of describing how to intentionally increase your training volume after a race, says Elisabeth Scott, an RRCA-, USATF-, and UESCA-certified running coach and the founder of Running Explained. “The taper is a very specific reduction in training load in the run-up to a race with the idea of maintaining race day fitness and decreasing training fatigue—something you can’t reverse,” she explains. “What you can do, though, is intentionally and systematically increase your training load after your post-race recovery period to safely return you to ‘normal’ training volume.”

To do that, you can look at the weekly mileage you had going into the marathon and mirror it as you return to running. In my case, I ran 36 miles the week of the Tokyo Marathon (30 to 35 miles was a comfortable base for me at the start of that training cycle); that was broken down into a 45-minute easy run, a 35-minute easy run, and a 20-minute shakeout. In a reverse taper, I would flip that same schedule.

Beyond the physical benefits of a reverse taper (more on that below), what I love about it is how it helps provide structure once the regimented schedule of your training program has reached its conclusion—i.e., the race. “Even if you have something on your schedule that says ‘walk for 30 minutes’, that allows you to feel like you’re accomplishing something and moving yourself forward,” says Scott. And feeling empowered, especially if you’re susceptible to the post-race blues, is going to keep you motivated—even if you don’t have a next race on your calendar.

Why is the reverse taper important?

For a lot of people (hi, it’s me), the first runs back after a race feel aaawful. That’s normal. A long-distance race effort taxes your energy resources; places huge loads on your tissues, tendons, and bones; causes microtrauma in your muscle cells; disrupts hormonal processes; and causes emotional fatigue. It can take up to four weeks for your body to fully recover physiologically from “massive aerobic exercise”—read: a marathon—according to older research published in Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

This is why actually taking time off after a big race is so important! Scott recommends taking at least a full week, I try to encourage people to take two. Thanks to the potent combo of marathon racing, jet lag, and gallivanting across Japan, I personally took a full three weeks off after the Tokyo Marathon.

Yea, you may lose a little fitness during that time. A loss of cardiovascular fitness and endurance starts to happen after as little as 12 days of no exercise, a 2020 literature review published in Frontiers in Physiology found. But, that’s inevitable: “You cannot maintain peak race day fitness forever,” says Scott.

Training isn’t linear; taking time off actually makes you a stronger athlete in the long-term. “A race is a very demanding effort, and the post-race recovery period is designed to help you get out of that hole,” Scott explains. “If you start too soon, you’ve basically got one foot in the hole, meaning you’re at a disadvantage. But if you recover properly, you’re starting with both feet on level ground, which sets you up for a stronger foundation.”

Before you freak out, “losing fitness” doesn’t mean you’re resetting to zero. “Fitness doesn’t just drop off a cliff—it begins to decline,” says Scott. And here’s an important distinction: “People often don’t understand the difference between fatigue and a loss of fitness. They go for a short run a week after a race and struggle to finish and think ‘I’ve lost so much fitness because I took a week off’ when it’s actually that they’re still so tired from the marathon.”

It’s funny, because post-race is when you can really afford to take that extra time off. When you’re increasing volume during training, it’s important to be cautious about making jumps that are too big for your body to handle (hence, the 10 percent rule—which, FYI, might not actually be the best way to increase your mileage safely). “When you’re returning to training volume after race day, though, it’s a place you’ve been before,” says Scott. “So you can get there more rapidly than you did the first time.”

OK, so how do you do the reverse taper?

I showed up at my weekly run club 20 days after the Tokyo Marathon (during which I did no exercise except a half-hearted attempt to ski the slushy snow in Niseko), and thought I could run the standard eight-mile route at an easy pace. LOL. Once we started, I quickly recalibrated that down to an hour, and then stopped at 45 minutes and took a scooter back to the start. Don’t be like me.

Remember, a reverse taper should mirror your race taper. What I should have done was a 20-minute shakeout, a 35-minute easy run, and a 45-minute easy run, which would have totaled about 20 miles. Then I could have built back up to 35 miles over another week or two. That obviously breaks the 10 percent rule, but 35 miles isn’t new to me—it’s my normal.

A traditional four-week post-marathon reverse taper might look like this, says Scott: “Take a week off completely, go for some restorative walks to facilitate recovery. In that second week, go for three 30-minute, easy effort runs on alternate days. Maybe you do 45 or up to 60 minutes on the weekend. I don’t like to add faster running or strength training until at least three weeks post-race—there’s no rush to add back in fancier, sexier stuff; that will come with your next training cycle.”

The focus of the reverse taper is on getting back to your normal base volume (and, for the love of god, do not compare your return to anyone else’s on social media post-race!). FWIW, “you may need up to eight weeks to do that!” says Scott. “I want to normalize that; especially after really intense races, you might need more than four weeks to get back to what’s normal for you.”

Remember, unless you’re actually a professional runner, you’re not making a living off this. And running should add to your life and your wellbeing—and that sometimes might just mean doing a little less.

the rundown

Hoka Rocket X 2

Sometimes you just put on a shoe and you’re like oh yea, this is IT. I don’t often feel that way about Hoka shoes; I know people love them Bondi and Clifton, but those just don’t feel great on my feet. The Rocket X 2, however… It sort of felt like a mix between the New Balance SuperComp Trainer and the Adios Pro, two shoes that I love. It’s got a full Peba midsole and carbon fiber plate, which made it incredibly lightweight and bouncy. It’s also way softer than most Hoka shoes, praise be. My only concern over longer distances would be the 5mm drop (will it go negative?!), but this is definitely a shoe I’d wear on race day.

“Choosing to Run,” Des Linden

I’m happy to confirm that Des Linden is as relatable in her new memoir—which comes out April 4—as she is on Twitter. I loved the way this book alternated chapters detailing her chronological life story with chapters breaking down her experience during the 2018 Boston Marathon. Even though I knew the outcome of that race, I found myself totally hooked on the way she explained her race day mindset and strategy. Linden is one of the more introverted pros (despite her Twitter witticisms), so I really appreciated getting a closer look at some of the more personal aspects of her career (including her relationship with her trainers and her health) as well as her willingness to talk candidly about what comes next.

How Accurate Is Your Wearable?

I think my love of data is well-known at this point, but I’ll be the first to tell you I don’t think my wearables are always accurate—especially when it comes to heart rate, which is a key measurement for many other data points (like training status or marathon level). Turns out, wearable devices have as much as 20 percent error when measuring heart rate, and caloric expenditure measurements can be off by as much as 100 percent, according to a new report. Exercise intensity, motion of extremities during exercise, wrist position, interference between skin and sensors (sweat or dirt on the skin), and skin pigmentation have been shown to decrease the accuracy of wearable devices, so, you know, that’s all great for runners!

You Don’t Need to Adjust Your Training to Your Menstrual Cycle

There’s been a lot of talk—thank you, TikTok—recently about menstrual syncing, or adjusting how you eat and exercise based on the phases of your menstrual cycle. With most fitness trackers offering menstrual tracking, it can kind of feel like another metric to optimize (Tonal literally just dropped a cycle syncing strength training program with the promo language “Did you know your period can actually be your training superpower?”). But a new study from Frontiers in Sports and Active Living determined that evidence does not support widespread recommendations to adjust your training based on your menstrual cycle phase. I do think being aware of where you are in your cycle can help you navigate training in a smarter way (or just give yourself a little grace), but you don’t need to reinvent the wheel here.