Why Do We Lose Our Sh*t During the Marathon Taper?

Welcome to taper town, when all rational thinking goes out the window.

No matter how well (or badly) my marathon training goes, there’s always some weird “injury” that pops up in the two weeks before the race that immediately sends me into a downward spiral of self-doubt, to the point where I’m not sure if I’ll even be able to start the race let alone finish it. (I’m preparing for marathon #13. This has happened before almost every race.)

First, nerves are normal—running a marathon is a BFD, whether it’s your first one or your thirteenth. Second, the taper part of training is notorious for turning even the most experienced runners into cranky, insecure toddlers.

The taper refers to the period before your race in which you strategically reduce your training load, which allows your body to replenish depleted energy and hormonal stores and repair cellular damage caused by the stress of training. For a marathon, the taper is generally two to three weeks; for shorter races, it can be anywhere from a couple of days to two weeks. (FWIW, a three-week marathon taper was shown to speed up recreational runners’ finish times by approximately 2.6 percent, or an average of 5 minutes and 32 seconds, in a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.)

But when you scale back your training, “your brain isn’t getting the endorphins, serotonin, or dopamine that it’s used to,” says Hillary Cauthen, Psy.D., a clinical sports psychologist and mental performance consultant. “It’s like a sugar crash.” The point of tapering is storing all that energy from training so you can deploy it on race day; in the meantime, it’s trapped within you.

What are the taper tantrums?

That unreleased energy can manifest in “the taper tantrums” or ““taper crazies”: mood changes, self-doubt, phantom injuries, and sudden illness.

When you’re not filling your time in the way that you used to, “you can feel a shift in your mood and can get irritable, cranky, and lash out,” says Cauthen. Not only are you not getting the chemical high you’re used to from regularly cranking out miles, you’re purposefully limiting your access to what may be a significant coping mechanism.

The taper also signals the end of a training cycle. “It’s like the light at the end of the tunnel, but it means the event is almost here, which can be stressful,” says Megan Cannon, Ph.D., a sports psychologist. “You’ve put so much time and energy into training for something that’s important to you, so it’s normal for the ‘what ifs’ to creep in and for you to start wondering if you did enough to reach your goal.”

It’s not just in your head. People get stomach aches, rapid heart rate, back and leg pain—it could be anything. That may be a somatization of stress, says Cauthen: “By not fully dealing with the stress of race day, our body’s are like, ‘I will trap it and hold it in.’” Or it could be as simple as with more rest, your body has an opportunity to work out some of the aches and pains that you tamp down during training. And “with less going on, your experience of pain is going to be different,” says Cannon. “You’re paying more attention to it.”

And it could be more than aches and pains. In the three to 72 hours after an intensive training session, your immune system may be suppressed, according to research published in the journal Sports Medicine—meaning it might be easier for viruses and bacteria to take hold. But during training, you’re likely adding additional load to your body before those 72 hours are up, which doesn’t give your body a chance to do anything about that. “It’s like you’re in a little bit of a survival mode,” explains Cannon.

When the taper comes around, though, that decreased training load means it’s safe for your body to calm down, she adds, allowing your immune system to kick back in and finally deal with any lingering issues—and you may actually come down with a cold or other illness (but you still have time to recover!).

How to temper the taper tantrums

So many runners dread the taper. But it’s a crucial part of training, and reframing it can make it much easier on you—physically and mentally. “We don’t often view rest as the final part of our training,” says Cannon. “Rest is not unproductive. If you don’t rest, you’re limiting your adaptations. So approaching a taper successfully means accepting rest as an intentional part of the cycle.”

How exactly do you do that, though? Well, this is where mental training comes in. “When the brain is stressed, our capacity to think rationally decreases,” says Cannon. “A little freakout is natural, but having steps and tools prepared can help. Focus on what you know heading into a race—the facts and logical truths. And when your brain starts spiraling, you can redirect it.”

If self-doubt is getting the best of you, “the only way to reduce the fear is to answer the fear,” says Cauthen. “Think of it like being scared of the dark—you can’t avoid the dark, but you can use a nightlight to make sure there’s no scary monsters.” In this case, the scary monsters are your fears. Pay attention to each one, and work through them with a plan: What will you do if the weather is terrible? What will you do if you get a cramp during the race? Prepare yourself for any scenario.

And when your body feels out of your control, start incorporating meditation and mindfulness (a 2020 study published in Neural Plasticity found that mindfulness training can actually give your endurance performance a boost). “Progressive muscle relaxation—in which you tense and then relax particular muscle groups—trains your body to relax when you’re in a state of stress,” says Cauthen “Deep yoga is another way to release emotional stress you’re physically carrying through functional movement.”

Instead of approaching the taper with apprehension, figure out what would make the downtime more enjoyable. “We do need to shift and say ‘what am I going to fill my time with?’” says Cauthen. “Finding things that you’ll look forward to during the taper—a sports massage, a pre-race day manicure—will help counterbalance the emotional depletion that you get from not running as much.”

Thanks to ASICS for their support!

I’ve logged over 100 miles during Tokyo Marathon training in ASICS’ new Superblast. This super shoe doesn’t use a carbon plate, but stacks a huge hunk of the brand’s FF Blast Turbo foam (used in the Metaspeed) atop a layer of soft, bouncy FF Blast+ foam (found in the Novablast). The result: A lightweight, highly responsive shoe that you can trust not to beat your legs up during easy long runs, but still deliver the speed you need on race day (like at the Rose Bowl Half Marathon just last month). Check them out on asics.com.

the rundown

“The Way of the Runner,” Adharanand Finn

I like to read books related to the place I’m visiting when I travel, so The Way of the Runner was a win-win: It’s about Japan’s running culture. The book focused mostly on the ekiden—a long-distance relay race—but the country’s obsession with running, not just as a form of exercise but a bonafide sporting event, was clear, and got me super pumped to experience the crowds around the marathon. Finn’s attempt to fully immerse himself in the elite ekiden culture was kind of a miss, but I did get a sense of how much of a team sport running is there, which I could really appreciate based on my experience running with a club in Denver.

Are Super Shoes Leading to More Injuries?

Carbon-plated running shoes change the biomechanics of the foot and ankle, which may cause bone stress injuries (especially to the navicular bone in the middle of the foot), a 2023 study in the journal Sports Medicine found. There are pros and cons to running in super shoes, which I wrote about in a 2021 story for Runner’s World, but don’t freak out about your Metaspeeds just yet: This study only included five cases, which is a teeny tiny sample size. Instead, use this as a reminder to always buy the shoes that feel best to you, no matter the marketing or social media hype, and if you are experiencing foot pain, talk to a professional to get to the bottom of the issue.

Lynn Jennings Exposes Coach’s Abuse

The Boston Globe published a heartbreaking story last week detailing how Olympic runner Lynn Jennings took it upon herself to expose sexual abuse by a former coach when she was a teen. (It’s the latest in a string of unsettling reveals, most notably the recent investigation that uncovered allegations of sexual abuse in the women's running program at Huntington University.) She discovered the coach had been “violating ethical boundaries for nearly a quarter-century,” and even when athletes did report him, he was quietly dealt with by Wellesley College, where he coached, instead of ever being subject to criminal prosecution. The whole story is pretty horrifying, and you can read more from a coach who worked with the abused over at Fast Women.

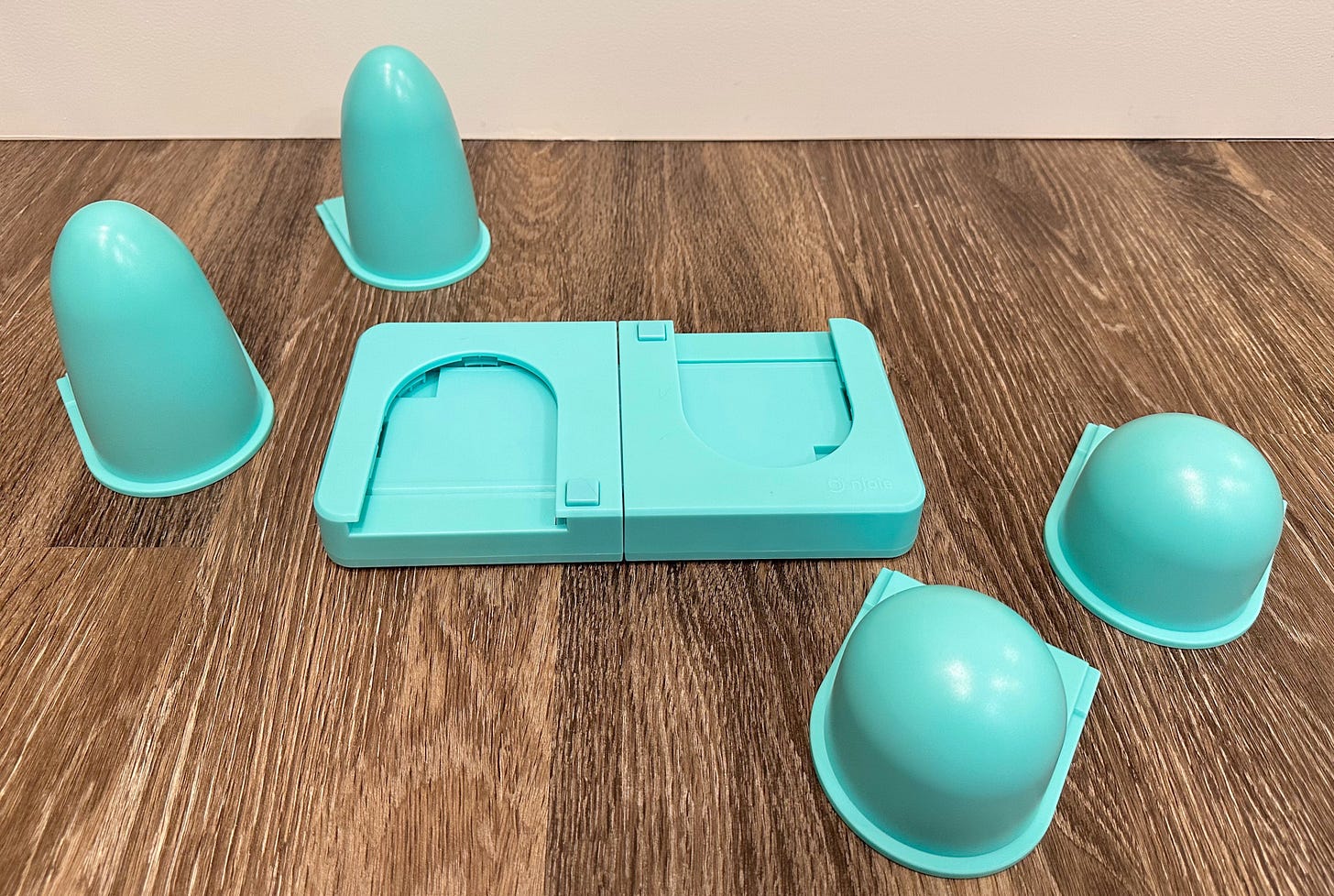

MFLEX Deep-Tissue Massage Tower

This massage tower was pitched to as a way to massage the psoas muscles (which start at the lower part of your spine and extend through your pelvis to your femurs) and reduce hip pain. Since that’s been a weird issue for me this marathon cycle, I decided to give it a try. Basically, you drape yourself on top of it like you would over a foam roller and let the interchangeable heads (the shorter ones are less intense, the taller ones are more intense) dig into your muscles until they release. I wrote a full review for CNN Underscored, but TL;DR: I’m not replacing my foam roller, massage gun, or sports masseuse with this any time soon—especially for $99.

Dahlie Winter Wool 2.0 Tights

Denver’s temps dipped back into the single digits last week, which was the perfect opportunity to test out these new-to-me running tights ($140, dahlie.com). I thought the three layers might feel bulky, especially with the soft shell over the front upper leg, but they didn’t feel restrictive in terms of movement (I liked the articulated knees) or breathability (mesh panels on the sides helped balance out the soft shell on the front). And the high waist was perfect, although I wouldn’t have minded a pocket in there somewhere.

I usually refer to it as pre-marathon paranoia. A few weeks ago, I was talking about it to someone in my regular running group as she was leading into her first half marathon and had a minor injury that she was obsessing about.