We Need to Talk About Easy Runs

I promise, slowing down will make you faster in the long run.

How fast did you run your most recent easy run? Chances are, it was too fast.

Most runners default to the most energy efficient pace, not the easiest pace, according to research in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology. In doing so, though, you’re cheating yourself of the benefits that come with running easy.

Training in the “gray zone”—AKA pushing too hard too often, and not running slow enough often enough—is one of the quickest ways to run yourself into a rut. That’s why polarized training and the 80/20 method prioritize doing 70 to 80 percent of workouts at a lower intensity (that’s your easy runs) and 20 to 30 percent at a higher intensity. When you’re running in that gray zone, your body never has a chance to truly recover, so you can’t max out your potential during harder efforts.

I know, it can be hard to slow down. It’s hard because it feels awkward at first, it’s boring, it feels like you should be doing more. But trust me: If Eliud Kipchoge, who averaged a 4:34 per mile when setting the marathon world record, can clock 8:45s on his easy runs, and Olympic marathon bronze medalist Molly Seidel can run a 9:00 pace during her warmups, you can run even slower.

In a sport governed by the clock and where athletes share every step via fitness tracking and social media platforms, it can almost feel like a bad thing to broadcast slower paces. But, FYI, the volume of easy runs was most correlated with world-class long-distance running performance scores—compared to tempo runs, long-interval training, and short-interval training—in a 2021 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Not sure if you’re running easy enough? Here’s what you need to know.

What exactly qualifies as an easy run?

In a general sense, an easy run is a low-intensity effort. That’s going to look different for everyone, though. You’ll frequently hear easy pace referred to as “conversational pace,” but that’s not my personal favorite guideline because I know I’m still capable of carrying on a conversation while running way faster than what should be my easy pace (that’s not a testament to my aerobic strength; more an issue that I’m mostly incapable of shutting up while I run).

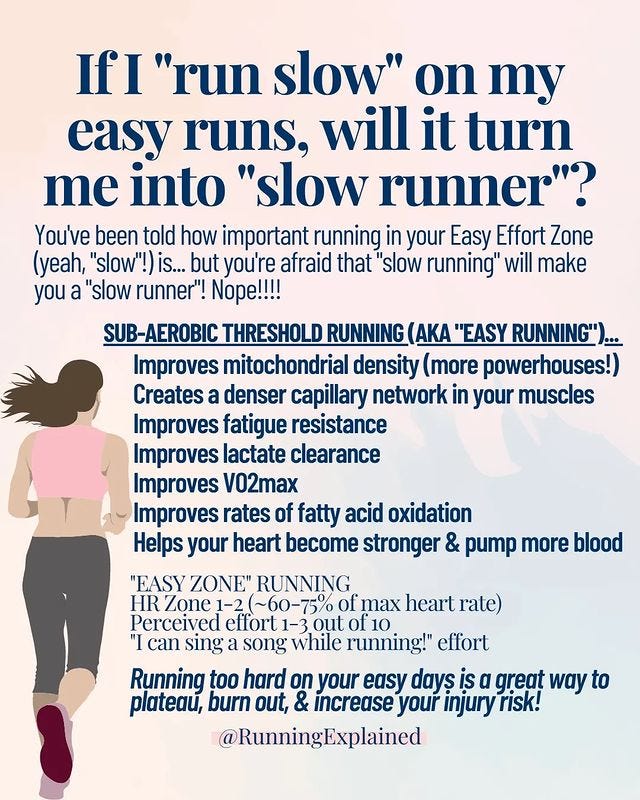

Of course you can pay attention to your breath (you should be able to hold a full conversation without sounding labored), but heart rate is another great metric to go off of. An easy run should fall solidly in Zone 2 training, meaning you’re below your aerobic threshold and your heart rate is 60 to 70 percent of your max.

If you don’t wear a heart rate monitor, that’s OK. Instead, use your rate of perceived exertion (RPE), a more subjective assessment that ranks how physically and mentally difficult exercise is for you in any given moment. An easy run should feel like a 2 to 4 on a scale of 1 to 10. RPE is a great measurement, because what feels “easy” to you may change day to day depending on external factors, like whether you drank last night, how well-fueled you are, and how much sleep you got.

For people who really prefer having a specific pace to stick to, your easy pace should be two or more minutes slower than your 5K race pace. Yes, two-plus minutes. Remember Kipchoge? His easy pace is almost twice as slow as his marathon pace. The point is, during easy runs, you should feel comfortable and relaxed, like you could run at that pace forever.

OK, but why should you run that slow?

Running slow—slow enough that you’re not taxing your body and incurring the need for additional recovery—leads to fundamental physiological adaptations that will improve your performance at faster paces.

Speed work acts almost like strength training, developing your muscles (thanks to increased ground reaction forces), while slower running helps your tendons, ligaments, joints, and bones adapt to the stress of running. When you’re running at that easier effort, you’re mostly using slow-twitch muscle fibers (which fire repeatedly with minimal fatigue) compared to fast-twitch muscle fibers (which are best suited for short, explosive efforts).

Slow-twitch muscle fibers have a higher density of mitochondria (known as the power plants of your cells, because they generate most of the chemical energy needed to power the cell's biochemical reactions) and greater capillary density.

The benefit of training those slow-twitch fibers is twofold: First, aerobic exercise increases the number of mitochondria in your cells, according to research published in the American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism, and the more mitochondria you have, the more energy you can produce. It can also increase capillary density by more than 25 percent, an older study in Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis determined, which improves blood flow to the muscles so they’re better able to use oxygen. Both outcomes translate to improved performance at faster speeds.

Active recovery—like an easy run—after strenuous exercise cleared accumulated blood lactate faster than passive recovery in a study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences. The ability to clear lactate from the blood allows the body to convert it back to energy so we can run long at a given pace. Easy runs also help improve your resistance to fatigue, and are a great form of mental training; running slower than you prefer teaches you to deal with physical discomfort.

Let’s normalize running easy, please?

For the record, there’s almost no limit to how slow you can go, as long as you’re not compromising your form. That’s one of the things I love the most about easy running: It democratizes a run. I can run with friends who race more than two minutes per mile faster than me or two minutes per mile slower than me. It connects me with different people than I do workouts with, and connecting with other runners is my favorite part of the sport.

I haven’t always been good at running easy, but I’ve really tried to embrace it this marathon training cycle by running my easy runs at 90 seconds to two minutes slower than my goal marathon pace. Even so, I’d love to separate the word “slow” from easy running. Yes, if you’re going by the clock, you should be running slower than your workouts or race pace. But the word “slow” can have negative connotations, so instead of pushing the pace for ego’s sake, I wish more people would be willing to pump the brakes and join the “party pace” crew. Consider this your official invitation.

the rundown

Saucony Endorphin Elite

OK, obviously this shoe came out last week and the “embargo” has been broken since it first leaked at TRE in November, but I’m allowed to actually review them now. I did a quick breakdown of the high-level selling points on Instagram, but after logging 20 miles or so in the Endorphin Pro here’s what I think: I felt fast in these, kind of like the first time I put on the Alphaflys. I highly doubt the foam provides 95 percent energy return, but I did feel a lot of forward propulsion without sacrificing stability. If you like the Endorphin Pro, I think you’ll like this even more for race day.

Someone Used ChatGPT to Devise Running Training Plans

It was inevitable, right? The author of this MIT Technology Review article asked ChatGPT to create a 16-week marathon training plan and it first suggested a max long run of 10 miles and then suggested running 19 miles the day before the race. Yiiikes on both accounts. Coaches, rest assured, your jobs are safe—for now. I think there is a place for AI in fitness, but it should be used in context with guidance from real humans and listening to your own body. Oh, and the author pointed out that “some entrepreneurs are even packaging up ChatGPT fitness plans and selling them”—for the love of god, don’t buy those.

SunGod Ultra Sunglasses

I love finding new sunglass brands! I just got the SunGod Ultra in for testing, and the frameless oversized design is right up my alley. The company claims their 8KO lenses—made from a 2mm nylon that’s lighter than polycarbonate (used by brands like Tifosi)—are the “most advanced on the planet,” and while that feels like maybe a stretch, I liked their clarity and how lightweight the frame felt. They also offer free customization, so you can pair your favorite color lenses with different frame colors (including options made from recycled materials), icons, and earsocks.

How Much Will a Gap in Training Hurt Your Race?

Missing a few runs during winter training is pretty much a given, considering how many viruses are spreading right now. Researchers—who published their findings in the journal Frontiers in Sports and Active Living—analyzed Strava data from nearly 44,000 runners who had completed a marathon after missing at least seven consecutive days of training during a 12-week build-up and compared that to their performance at another marathon with no training disruptions. More than half had at least one gap of at least seven days during their 12-week marathon build-up, and nearly a third had a ten-day gap; those who missed a 7- to 13-day stint of training ran 4.25 percent slower than when they had an uninterrupted build-up, and those who missed even more time ran even slower. Moral of the story: Don’t freak out about missing a day or two, but you might need to reset your goals if you miss a week or more.

Agreed on easy running and the Endorphin Elite, lol at ChatGPT training plans, disagree on SunGod - they look good but I found the performance lacking, and, after having a gap myself due to Covid before NYC, 4.25% slower was very close to what I experienced.

Thanks for sharing this Ashley! It's something I've been actively working on now through the build phase of my training. My coach, Eric Orton, is one of the advocates of coaching runners to slow down and focus on form and cadence. I cringe at my mile splits sometimes and get into a case of comparisonitis, but then I recognize that I've improved form and haven't had the injuries that I previously had.

Also on ChatGPT... INSANE. What is happening to the world.